The Situation on the Poland-Belarus Border: Background, Geopolitics, Narratives

The Situation on the Poland-Belarus Border: Background, Geopolitics, Narratives

What is now taking place on the Poland-Belarus border was triggered by a political crisis in Belarus that has unfolded since August 2020. Back then, Belarusian strongman Alexander Lukashenko, in power since 1994, was declared winner of a presidential election that opponents and the West said had been rigged.

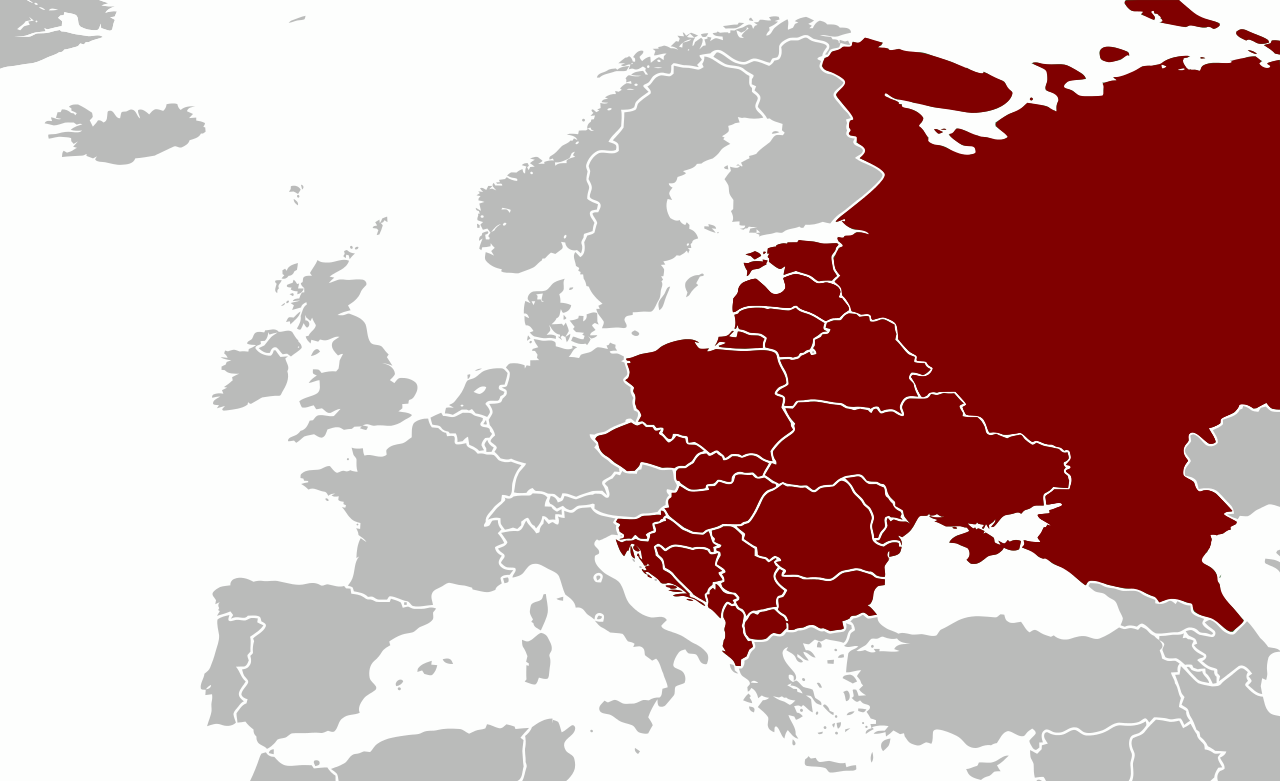

- For weeks, thousands of migrants, mostly from the Middle East, have been found themselves stranded at the borders of Latvia, Lithuania, and Poland in an attempt to reach the European Union. Now they are gathering at the border crossing in Kuźnica.

- Through an orchestrated operation the regime in Belarus is now conducting, a manufactured migrant pressure is at Poland’s door––and thus that of the European Union––in response to a round of sanctions the bloc imposed in June amid the rigged presidential vote in August 2020 and the mass crackdown on opposition figures and journalists.

- What is known as the “migrant crisis” on the Poland-Belarus border is a form of hybrid warfare staged by Belarusian special services, where Russia plays an unofficial role. The geopolitical context of the current situation on the border and events over the past months include also military preparedness of NATO’s eastern flank, the European Union’s authority worldwide, and the energy security of Ukraine and EU nations.

Background

On August 9, 2020, Belarus’s electoral commission said Lukashenko secured 80.1 percent of the vote in the poll, with the turnout of more than 84 percent[1]. In May and June, some independent polls found that Lukashenko could win roughly 7 percent of the vote while a July 2020 poll from Belarusian state broadcaster ONT put the strongman at nearly 70 percent of the vote. No observer mission from the OSCE’s Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (ODHIR) was invited to Belarus[2]. Amid unrest in the Eastern European country[3], Lukashenko’s top rival Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya, who was widely believed to be the real winner of the election, left the Belarus as she feared repression.

Protests were held in Minsk, the country’s capital, state factories, and in front of Belarusian embassies across the globe, also in Warsaw. Protesters took to the streets to challenge the vote while Lukashenko responded with a bone-shattering crackdown on opposition figures and independent journalists[4].

Human rights abuse and the repression of civil society in Belarus sparked outrage worldwide. All EU nations, the United Kingdom, the United States, Canada, most South American states, Australia, Japan, and Israel have refused to recognize Alexander Lukashenko as the legitimate president of Belarus. In their statements, NATO, the UN, and the OSCE voiced concerns about the rule of law and human rights while the European Council refused to recognize the official result and condemned unacceptable violence against protesters. In addition, it earmarked €53 million to support the Belarusian civil society, mostly in the form of coronavirus emergency support, and introduced sanctions targeting the regime[5]. In August 19, 2020, remarks, Ursula von der Leyen, the president of the European Commission, promised the bloc would sanction all those responsible for violence, repression, and falsification of the results of the election.

On October 2, 2020, the European Union imposed sanctions on 40 Belarusians in response to repression against demonstrators in its first-ever batch of punitive measures following August’s contested election. By June 21, 2021, the bloc introduced four packages of sanctions on people and entities linked to the Lukashenko regime. The European Union also targeted Belarusian petroleum products in a move that dealt a blow to the country’s economy. In June, the EU slapped economic sanctions on Belarus in response to a “state hijacking” while the plane was flying from Athens to Vilnius on May 23, 2021, to detain a Belarusian opposition figure Roman Pratasevich and his girlfriend Sofia Sapiega[6]. In Belarus Pratasevich has been charged with inciting hatred and riots––if convicted, he could face up to 15 years in prison or even the death penalty[7].

The origin of migrant pressure

In retaliation for EU sanctions and criticism, Alexander Lukashenko has waged a hybrid conflict against the bloc since June 2021, cynically using migrants, mostly from the Middle East, as weapons. Belarus’s efforts target notably Poland and Lithuania as both stood openly with the opposition in Belarus after the electoral fraud and sheltered opposition leader Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya.

This summer, Belarusian special and border services began transferring people from the Middle East seeking to enter Western Europe along the country’s border with Poland, Lithuania, and Latvia. In an October 8 statement, the authorities in Poland said the attempt to deliberately incite illegal migration along the Poland-Belarus border is a well-orchestrated operation. The authorities in Belarus control migrants who are trying to cross from Belarus to Poland. This is evidenced by such official documents as invitations, permits, or state hotel bookings in Belarus[8]. Papers were leaked to confirm the involvement of Belarusian authorities.

As the situation on the border between Poland and Belarus has been developing dynamically in recent months, border guards in Poland, Lithuania, and Latvia recorded numerous attempts to illegally cross the EU’s border. Adam Eberhardt, the director of Warsaw-based Centre for Eastern Studies, said that by destabilizing the EU’s eastern regions, Alexander Lukashenko used thousands of migrants from the Middle East who arrived in Belarus through facilitators such as Centrkurort, the state-owned Belarusian travel firm run by Lukashenko’s older son, Viktor, to achieve both economic and political goals[9]. Targeting Western nations, Belarus’s operation is intended to weaken[10] the European Union and expose its border vulnerabilities.

What is known as Belarus-affiliated “travel companies” offer migrants a route into Europe through the Poland-Belarus border. Migrants from the Middle East are offered aid to slip into the Schengen area illegally. Travel companies provide flight, accommodation, transfer to the border and necessary assistance, and sometimes further transport into Western Europe. The trip costs between a few to several thousand dollars per person, which is an addition to the regime’s budget.

Importantly, through its “travel firms,” Belarus is bringing some 3,500 people each week, which means huge financial gains for the regime[11]. A total of 70,000 flights were reported to Minsk from Turkey, Egypt, countries of the Caucasus and the Middle East from early 2018 to November 8[12]. However, Lukashenko is hoping to replay the “Turkish scenario,” when the European Union provided Ankara with some generous assistance to halt the influx of migrants into Europe.

In response to a spike in attempts to cross the border from Belarus, a localized state of emergency was introduced in 183 Polish municipalities on September 2. On September 28, Poland’s parliament extended a state of emergency by 60 days[13]. The country bans reporters and aid workers from the border area; only state services are allowed to enter the zone.

The law on the construction of the state border security came into force on November 4[14]. On the same day, Poland’s interior ministry convened a press conference that was attended by Interior Minister Mariusz Kamiński, Deputy Commander in Chief of the Border Guard Wioletta Gorzkowska, and Marek Chodkiewicz, the plenipotentiary for the preparation and implementation of state border protection[15]. Kamiński referred to the wall as a “strategic security undertaking.” The 180km long and 5.5m-high wall on Poland’s border with Belarus will be topped with barbed wire. It will be fitted with motion sensors and night-vision cameras. The wall is expected to cost around PLN 1.6 billion and will be ready by the first six months of 2022. The wall is a temporary solution, according to the interior minister. Other EU neighbors of Belarus also reinforced their border security mechanisms[16].

Mounting tensions

Tensions rocketed on November 8, 2021, when hundreds of migrants massed at the Poland-Belarus border near Kuźnica, seeking to force their way through. Since then, Polish border guards have recorded hundreds of attempts to illegally cross the border each day. More incidents were reported within the past two weeks, with the most recent one close to Czeremcha, where some 200 migrants attempted to break through a fence on the Polish-Belarus border[17]. The regime is weaponizing people to enter illicitly from Belarus whose officers manufacture the whole operation. Sometimes armed Belarusian officials pushed migrants right onto barbed wire fencings.

People seeking to enter Poland are being incited by the regime to attack Polish officers. In addition to Belarusian state-run broadcasters, also those creating an atmosphere of hatred are KGB and GPK officers who verbally abuse Polish soldiers and border guards, throw stones, and blind them with laser beams[18]. On November 16, Polish border guards, policemen, and soldiers fought off an attack by hundreds of migrants at the frontier with Belarus with water cannons and flash grenades at the border crossing in Kuźnica[19]. Several dozen officers have been injured in clashes since August 2021. At the border present was Vitaly Stasukhevitch, the head for the Public Security at the Department of Internal Affairs of the Grodno Region Executory Committee, who was in charge of suppressing anti-government protests in the Belarusian city of Grodno[20].

The situation on the Poland-Belarus border remains tense while Polish border guards report a few hundred attempts to break into Poland illegally. Stanisław Żaryn, the spokesman for the minister coordinating special forces, is providing daily updates about further attacks.

Geopolitics

It is vital to set the border crisis in an appropriate geopolitical context. Countries across the globe agree that Alexander Lukashenko, the illegitimate leader of Belarus according to the West, the national intelligence agency of Belarus[21] (KGB), the state border guard outlet[22] (GPK), and OCAM[23] officers are all behind a mass hybrid scheme consisting of bringing people from the Middle East to the EU’s door. The Kremlin has denied any Russian role in the crisis while there is evidence that Moscow took part in the operation, also by arranging flights from the Middle East to Minsk.

Through migrant pressure, Belarus and Russia are now waging a hybrid war against the EU. Clashes took place in media outlets and through open and classified diplomatic channels, as well as affected the economy and the energy, not to mention the border area where there were some incidents involving Belarusian officers shooting at Polish border guards. Belarusian operatives, perhaps in cahoots with Russian officers, spark incidents along the frontier, which is just a starting point for the whole information campaign in media outlets and online. With a raft of appropriate tools and mechanisms, it is targeting the European Union to undermine it worldwide.

Tensions rise high between both the European Union and Belarus, and between Russia and the North Atlantic Alliance. The chief adversary of NATO is Moscow whose hybrid operation seeks to cripple the Western military bloc. Geopolitics analysts say that the border crisis broke out close to the Alliance’s most vulnerable place, or the Suwałki Gap[24]. This 80-kilometer stretch of land between the westernmost Russian exclave of Kaliningrad and Belarus is strategic for the North Atlantic Alliance.

On November 4, Russian President Vladimir Putin and Belarusian dictator Alexander Lukashenko signed an agreement providing for a total of 28 integration “programs” at a meeting of the Supreme State Council of the Union State. The document focuses mainly on economic and regulatory issues, including common policies on the economy or energy. In addition, the two leaders approved a joint military doctrine[25]. The Russia-Belarus integration would take its toll on security along NATO’s eastern flank, notably Poland and Lithuania, as Russia would feel free to send its troops close to the Poland-Belarus border and the Suwałki Gap. The area is under full NATO intelligence and satellite surveillance while the Polish counterintelligence agency is seeing increased Belarusian and Russian activity in this region[26].

What was vital for the Poland-Belarus migrant crisis was the first face-to-face summit that brought together U.S. President Joe Biden and Russian President Vladimir Putin in Geneva this June. The meeting yet failed to make a breakthrough in U.S.-Russia relations. The men discussed Ukraine, Syria, cyberattacks, Afghanistan, Iran, disinformation, and the geopolitical importance of the Arctic. President Biden said he emphasized human rights issues in his meeting, including the imprisonment of Russian opposition leader Alexei Navalny and human rights abuses in Russia. On the table was also the situation in Belarus and turmoil after the (rigged) vote.

Geopolitically, it was the clash of the new U.S. leader with the Russian president that the former lost, according to journalists and columnists. Grzegorz Kuczynski, a Russian analyst at Warsaw-based think-tank Warsaw Institute, said after the Geneva summit that Vladimir Putin saw Biden as a weak opponent who gently responded to Russian malign actions targeting the United States (cyber attacks), avoided an open confrontation, and sought a compromise rather than a conflict[27]. The Geneva summit coincided with early efforts to exert migrant pressure on Lithuania and Latvia.

The tenure of Donald Trump differed in this respect. The Russian leader interpreted Biden’s conciliatory stance as a sign of weakness that he exploited in the geopolitical theater in Europe whose eastern countries––Ukraine, Belarus, and the Baltic states––the Kremlin believes to clutch in its exclusive zone of influence.

Russia plays its part in the energy crisis in Ukraine and some EU states and throws, albeit unofficially, support to the Belarusian dictator to exacerbate migrant pressure on the political bloc[28]. U.S. intelligence has reported that Russia amassed a total of 100,000 troops in eastern Ukraine close to what is known as the people’s republics of Donetsk and Luhansk. Moving Russian troops to eastern Ukraine sends a signal of combat readiness, an effort aimed at integrating the annexed Crimea with Russia and changing the balance of power in the NATO-controlled Black Sea region. U.S. intelligence has found the Kremlin is planning a multi-front offensive as soon as early next year involving up to 175,000 troops[29].

Massing troops along Ukraine’s eastern border is linked to the situation on the Poland-Belarus border and the energy crisis that torments both Ukraine and the European Union. Efforts to escalate tensions fit into Moscow’s geopolitical pressure when global oil and gas markets are seeing some turbulence. On November 1, 2021, Ukrainian officials announced that Russia had stopped thermal coal exports just as stocks were five times lower than the government’s expected volumes at this time of year. Furthermore, Russia is blocking all coal deliveries from Kazakhstan. Ukrainian Deputy Energy Minister Maxim Nemchinov said Kyiv was embroiled in an energy war with Russia[30].

Weaponizing energy resources is a salient feature of Russian foreign policy. The Kremlin is also pressing on the EU’s energy security amid suspended procedures to certify Nord Stream 2. Once operational, the gas pipeline would erase eye-watering energy prices, according to Russian officials. Back in August, Gazprom’s European gas storage facilities were just 18 percent full. Jakub Wiech, a journalist at Energetyka24 news service, said some 1.1 billion cubic meters (bcm) of gas were stored in the firm’s biggest facilities in Austria, Germany, and the Netherlands. “For the sake of comparison, Poland’s annual demand for gas is roughly 18 bcm. So Gazprom’s gas stocks in Europe would be enough for Poland for no more than a month[31].” The Kremlin is seeking to cut off gas mostly to promote Nord Stream 2, certify the pipeline before making it operational, sign long-term gas deals with EU countries, and consolidate Russia’s position as Europe’s number one energy supplier.

What also weighs heavily on the border crisis, Ukraine, and security schemes in Central and Eastern Europe is U.S.-Russia relations. In his article, Marek Budzisz insisted on a dual approach the U.S administration had adopted towards Moscow’s foreign policy. A more liberal and democratic stance presumes efforts to maintain diplomatic channels and ease tensions through pulling some U.S. contingents out of NATO’s eastern wing. According to Marek Budzisz, the purpose is not to “raise Putin’s ire[32].” Under a second scenario, whose proponent was John Bolton, the former national security adviser to Donald Trump, it is necessary to take firm action to the Kremlin’s provocation by dispatching military advisers to Ukraine or launching a military offensive in breakaway regions of Transnistria and Abkhazia. The incumbent U.S. administration prefers a less confrontational strategy towards Russia that Vladimir Putin sees as Washington’s consent to more aggressive steps in Central and Eastern Europe. This is why Russia is massing its troops near the Ukrainian border, orchestrating an energy crisis in the EU, and helping Belarus exert more pressure on the bloc’s border.

Narratives on the border crisis

With some recent events on the Poland-Border border, the border crisis narrative in Belarusian and Russian propaganda outlets have also evolved. Poland was being forced into letting migrants inside the Schengen area to ease the humanitarian crisis. Media outlets featured photos depicting migrant mothers and children suffering from cold weather and begging Polish officers to enter the country. Pictures showing starving and stranded people from the Middle East sitting by the razor-wire fence contained a narrative of cruel and inhumane treatment of migrants waiting on the Polish side of the border.

They were then disseminated by current affairs programs and social media channels. In addition, Russia and Belarus accused Poland of inciting what they named a humanitarian crisis, urging Warsaw to treat people humanely and allow them into Poland, which they both believed was the only solution to this conundrum. Pushing whole responsibility onto Poland is part of a propaganda operation engineered by the regime in Belarus. The narrative was a textbook example of a hybrid operation blending disinformation and a mass-scale propaganda offensive.

Aware of Poland’s resistance and failed propaganda efforts, Belarus shifted its tactics. On November 16, the regime brought hundreds of migrants to the Bruzgi-Kuźnica border crossing to let them illegally enter Poland. Polish authorities said migrants were trying to destroy a border fence and attack soldiers, a strategy that eventually fell flat. It is no doubt that Belarusian services played an active role in pushing people towards Poland. Possibly KGB or GPK officers coordinated illegal border crossing in Kuźnica and gave stun grenades to those seeking to cross the frontier.

Poland resisted the attacks while the migrants were huddling for a few more hours before dispersing in small groups along the border. The regime now tends to send small packs of migrants at night to less secure places along the border to get across the border through destroyed fencing. Amid the tenacity of Polish agencies and a proper information policy from the government, people seeking to arrive in Europe through murky travel firms learn that it is impossible to enter Poland from Belarus, a move that mitigates both migrant pressure and the hybrid operation. A poll from Instytut Badań Pollster found that Polish border and law enforcement agencies enjoyed the approval of 84 percent of Polish respondents while 16 percent of people thought differently[33].

It is vital to explain Belarus’s hybrid attack targeting Poland and the European Union in all media outlets, including social media channels. In a tweet, Disinfo Digest listed active measures Belarus used to exert border pressure on Poland and the European Union:

- Disinformation;

- Dislocation of migrants;

- Surveillance, observation, simulation;

- Damaging physical barriers;

- Planned migrant transfer (time and location);

- Coordinating border area locations;

- Recognizing the activity of the Polish Border Guard;

- Staging provocations and coordinating media content[34].

Distinct narratives on the hybrid operation along the Polish border now float in the media space. They fuel tensions within Polish society, foster related disinformation schemes, and shed a negative light on the authorities in Warsaw alongside the army and law enforcement agencies.

The Polish government refuses to allow migrants into the country and thus the visa-free Schengen area, which carves out a region within the union with no internal border controls. While in Poland, people could move towards other Schengen countries. Poland has been consistent since the migrant crisis broke out and the country’s border guards recorded very first attempts to illegally enter Poland.

Human rights activists and aid charities call for establishing a humanitarian corridor between Belarus and Germany and other Western countries to mitigate migrant pressure and thus pull back the border standoff. Many yet believe this solution could bring about far-reaching consequences as Moscow and Minsk might see this as a concession from the European Union and Poland, which could pave the way for bigger pressure and escalated tensions with the EU and NATO––also through new hybrid tools.

At the same time, Poland has refused additional support in the form of Frontex and Coast Guard Agency border guards. The country rejected the EU’s aid, claiming Frontex did not have appropriate mechanisms to seal the border and boost state security. Possibly the government in Warsaw fears some political costs in exchange for EU aid, notably amid its strains with Brussels[35]. Launched in 2021, the European Border and Coast Guard Standing Corps is the EU’s uniformed service within Frontex. By 2027, the corps is planned to number 10,000 personnel, although the agency’s website says there are 600 officers deployed to Schengen external borders[36]. For comparison’s sake, the Polish government said it had dispatched to the border area 9,000 soldiers and some 2,000 policemen to support border guard officers in Podlasie.

According to Elisabeth Braw, a Politico columnist, “the standoff on the border between Belarus and the European Union may be a crisis involving migrants—but it’s not a migration crisis. It is a geopolitical crisis[37].” The word “crisis” refers to the European migrant crisis (2015–2016) when millions of people have fled African and Arab countries across the Mediterranean Sea to escape war[38]. Back then, the European Union saw 2.5 million asylum seekers. The scale and reasons are incomparable to the fact that thousands are now huddled between the borders in Poland and Belarus. The Belarus border crisis is rather a “hybrid attack,” “geopolitical clash,” or a “politically engineered migrant pressure,” all of these accurately reflecting the true nature of this situation. For the government in Warsaw, it is vital to correctly name what is taking place in the border area to create a Polish narrative on security threats and combat Russian and Belarusian disinformation efforts.

Indeed, Poland denied journalists access to the border with Belarus, but for a reason. In this manner, the only source of what is taking place on the border is the Polish government to prevent disinformation schemes from circulating. Also, media outlets abroad could rely solely on official government reports. Moreover, any media outlets opposing the government are unable to feed rumors that could damage the country’s security and foster fear among members of society. The appropriate narrative about the situation on the Poland-Belarus border matters most for Poland’s security policy and its ties with the European Union, NATO, and other countries.

In addition, seeking to advance its national interests, Lukashenko’s authoritarian regime fails to respect democratic values: the rule of law, human rights, and the freedom of speech[39]. This explains Belarus’s frivolous propaganda campaigns, unbridled by any democratic “hurdles” typical for Western nations. As the worldwide community is short of legal tools to enforce stability in Belarus, the only punitive measure consists of economic, diplomatic, and information schemes. The purpose of the border crisis is that Belarus––and indirectly Russia––is seeking worldwide recognition for the regime and the relaxation of EU sanctions.

Worldwide reactions

In response to the hybrid campaign Belarus has waged since this August, the European Union is ratcheting up pressure on the country by imposing coordinated sanctions targeting the regime. In December, the bloc introduced the fifth batch of sanctions applying to a total of 183 individuals and 26 entities[40]. It freezes assets and bans Belarusian carriers from European airspace and airports[41]. “We will give the green light to extending the legal framework of our sanctions against Belarus so that it can be applied to everyone who participates in smuggling migrants to this country,” the European Union’s foreign policy chief Josep Borrell told a French newspaper[42].

Any economic sanctions hitting the country’s economy are the bloc’s usual response to Lukashenko’s wrongdoings[43]. Kamil Kłysiński, an analyst at Warsaw-based think-tank Centre for Eastern Studies, insists that sanctions make sense while serving as an efficient tool of pressure on some regime-linked industries yet it takes time to observe tangible effects[44]. The bloc’s restrictions target those Belarusian sectors that bring most money to the budget. The last-ditch solution would be cutting transit and freight traffic between Belarus and other countries yet this could be a blow to both Poland and Russia.

According to an article from Polish daily Rzeczpospolita, economic sanctions against Belarus cause little pain to the regime as trade with the country is now flourishing. It is just a “flick,” according to Romańczuk[45]. The strategy could yet backfire, targeting EU countries that trade with Belarus and Russia, albeit indirectly. Meanwhile, they are easy to circumvent sanctions through a chain of non-EU intermediaries. Nonetheless, a dramatic drop in EU-Belarus trade volumes could cement economic ties between Russia and Belarus, which is as bad as the situation now.

EU sanctions are just one of the tools hitting the Belarusian regime. Amid harsh migrant pressure, Poland, Lithuania, and Latvia could ask the military bloc to invoke NATO’s Article 4 that calls for consultation over military matters when “the territorial integrity, political independence or security of any of the parties is threatened[46]”. Talks are now underway and a meeting of NATO leaders of defense minister is a clear political signal to a potential aggressor that allied countries are never along in face of a conflict.

Poland called an Article 4 meeting in 2014 in response to the Crimean crisis. In consequence, allied forces were dispatched to Poland, not to protect the country’s territorial integrity, but to reaffirm allied support and guarantees[47]. In its statement, the UN Security Council “condemned the orchestrated instrumentalization of human beings whose lives and wellbeing have been put in danger for political purposes by Belarus, with the objective of destabilizing neighboring countries and the European Union’s external border and diverting attention away from its own increasing human rights violations[48].”

Seeking to build broad international support, Polish Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki made a European tour between November 21 and 26 to visit the Baltic states, attend the Visegrad Group meeting in Budapest,[49] and hold talks with his Slovenian counterpart in Ljubljana. He went to Paris, Berlin, and London for talks on the border crisis with the French, German, and British leaders. On November 25, President Andrzej Duda met with NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg to discuss security in Central and Eastern Europe. Both men condemned the regime’s cynical and inhumane exploitation of vulnerable migrants and promised to provide Ukraine with political and practical support[50]. Poland’s diplomatic efforts proved successful as some 1,458 Iraqis and Kurds had been repatriated, according to a BelsatTV article (November 27)[51].

It is challenging to predict Lukashenko’s next moves towards Poland, the Baltic states, and the European Union. Indeed, at a meeting of the Strategic Management Center of the Defense Ministry, attended by top interior officers and KGB and GPK officers, Lukashenka urged them all to remain prepared for any scenario[52].

The autocratic ruler has on many occasions chided on Polish officials and blamed them for the border crisis. Now journalists, current affairs specialists, and other experts need to predict the strongman’s steps, but it is first the task for government agencies in Poland and all Central and Eastern Europe and NATO states to monitor the situation while societies should take these forecasts with an element of unpredictability, which is typical for authoritatian regimes.