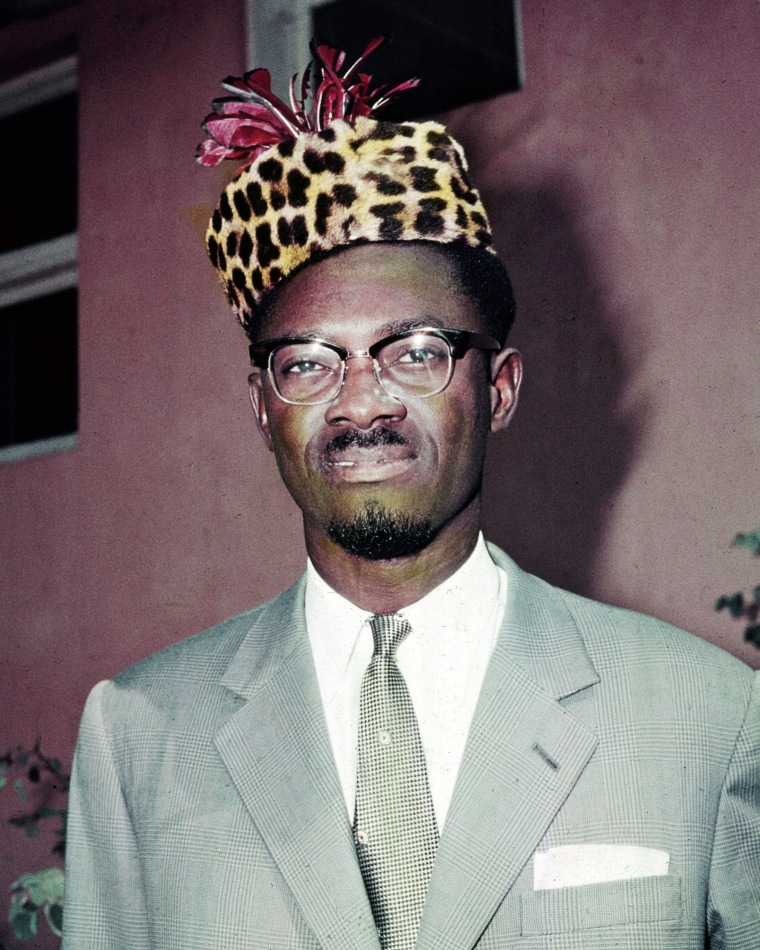

Slain Congolese icon’s tooth returned to family decades after killing

Slain Congolese icon’s tooth returned to family decades after killing

A tooth believed to have been ripped from a man who once carried a nation’s hopes of freedom and democracy is finally going home.

The symbolic handover of Congolese independence leader Patrice Lumumba’s remains is meant to soothe a family’s and a country’s historic pain, but it is also reviving memories of European colonialism and America’s covert war to contain communism.

While the restitution of Lumumba’s tooth Monday may be viewed as a chance for redemption by Belgium amid continuing global outrage over the 2020 killing of George Floyd, some accuse Brussels of exploiting the occasion without making a solid commitment to rectify its historical wrongs.

The return of what is widely believed to be Lumumba’s tooth means his family can finally have a “resting place where they can pray for their father,” said Brussels lawyer Christophe Marchand, who represents two of Lumumba’s five children, Francois and Roland. Without the remains, they can’t fully mourn, he said.

Roland Lumumba said Friday at a news conference in Brussels, “I can’t say it’s a feeling of joy, but it’s positive for us that we can bury our loved one.”

A Belgian official handed a blue box containing the tooth to members of his family at an official ceremony at Egmont Palace in the Belgian capital on Monday.

Following its handover to the family, Lumumba’s tooth will return to the Democratic Republic of Congo. Although exact details are unclear, a homecoming tour is expected to take the relic to Lumumba’s home village, ending with an official burial in the capital, Kinshasa.

African sovereignty

The Democratic Republic of Congo, or DRC, gained independence from Belgium in 1960. Lumumba’s election as the independent DRC’s first prime minister shortly beforehand brought hope that the break with colonialism would bring about a real democracy.

“We were so hopeful that independence would mean progress, better working and living conditions, more prosperity, using our national resources for the well-being of our people,” said Georges Nzongola-Ntalaja, a professor of African studies at the University of North Carolina.

To many Congolese, Lumumba is a national hero and a “standard bearer of the Congolese independence movement,” said Nzongola-Ntalaja, who has written extensively about Lumumba’s rise from postal clerk and beer salesman to leader of a nation. “We consider Lumumba to be a great chief and a great leader.”

His reputation stretched across the continent, said Reuben Loffman, a lecturer in African history at Queen Mary University of London, who said Lumumba, a charismatic orator, was “somebody who stood up for African sovereignty in desperate circumstances and died for that belief.”

But at the height of the Cold War, Lumumba was also perceived as a Soviet sympathizer, alarming the U.S. and its Western allies.

Ousted by a Western-backed coup three months after he took office, Lumumba was abducted, tortured and assassinated in 1961 at the age of 35. His body was then dug up, dismembered and dissolved in acid by Belgian officers, one of whom said he pocketed a tooth as a “trophy.”

Thus Lumumba’s family and his country were deprived of a burial and a grave.

Lumumba’s assassination remains part of the “national trauma” for the Congolese, Nzongola-Ntalaja said, and it has had far-reaching effects on the nation. The new Congolese democracy unraveled in its wake, shaking the country the size of Western Europe.

In 1997, when the kleptocratic dictator Mobutu Sese Seko was deposed after 32 years in power, the country was left in chaos, with one of the highest debt burdens among developing nations. Today, despite the DRC’s vast mineral wealth, most of its people benefit little from their country’s riches. It’s home to the world’s third-largest population of poor people, according to the World Bank.

Although Belgium-backed Congolese separatists executed Lumumba in January 1961, an inquiry by the Belgian Parliament 40 years later established that certain members of the Belgium state at the time were “morally responsible” for the circumstances leading to his death. The prime minister at the time, Guy Verhofstadt, apologized in 2002 for Belgian involvement in Lumumba’s death.

Lumumba’s son Francois launched a separate inquiry into his death in Belgium in 2011, seeking to prosecute 10 Belgians for their connection to his father’s murder. It remains ongoing, with only two of the accused still alive.

But some people, including two of Lumumba’s sons, oppose the tooth’s restitution.

Guy-Patrice Lumumba said he believes the DRC’s current leadership is exploiting his father’s name to ease relations with Belgium, while the family still awaits justice.

“I don’t see how Belgium can take part in this ceremony” he told NBC News. “We have been waiting eleven years. We want the truth. We want justice to be pursued in the assassination of our father.”

The Belgian anti-racism activist Mireille-Tsheusi Robert said the restitution was a “marketing operation” that allows Belgium to improve its image without apologizing for its colonial wrongs.

“It is not simply by returning Lumumba’s tooth that we can repair a century of humiliation,” she said.

There are also lingering questions about the role the U.S. might have played in his death.

The State Department’s historic records reveal that the U.S. government launched a covert political program in Congo in 1960 lasting almost seven years, initially aimed at removing Lumumba from power and replacing him with a more pro-Western leader.

In 1975, a Senate committee investigating CIA plots to assassinate foreign leaders concluded there was a separate, failed plot by the U.S. to poison Lumumba, but it found no evidence that the CIA was connected to his killing.

Nzongola-Ntalaja said the Senate committee conclusion was “disingenuous” for ignoring allegations of U.S. responsibility in destabilizing Lumumba’s political standing.

“They concluded the CIA had no responsibility in this matter because they did not open fire on Lumumba,” he said. “They didn’t hold the gun and kill him, but the reality is the CIA played a major role in getting Lumumba removed from government as prime minister.”

The State Department and the CIA wouldn’t comment.

Lumumba’s death capped decades of violent colonial rule and foreign interference in what is now the DRC, so the return of Lumumba’s tooth is of “emblematic significance” for both nations, Belgian Prime Minister Alexander De Croo said last month.

The country’s monarch, King Philippe, reaffirmed his “deepest regrets” for his nation’s colonial-era abuses in the DRC during a visit to the country this month, but he stopped short of a formal apology. Belgium’s control of the vast region from 1885 to 1960 was marked by savage violence, during which millions of people were turned into a slave labor force, with mutilations commonplace and the nation’s natural resources plundered.

But regret isn’t enough, and Belgium should own up to its responsibility for its colonial past as well as Lumumba’s death, Nzongola-Ntalaja said.

In a statement to NBC News ahead of the restitution, the prime minister’s office noted that a parliamentary commission is underway in Belgium that will examine “the dark areas” of its colonial past.“ The DRC has been clear that it is “not expecting an apology from Belgium,” De Croo’s official spokesperson said, “but we now unite our efforts to build the future side by side.”

Tooth a ‘trophy’

The existence of Lumumba’s tooth came to light in a 1999 interview with Gerard Soete, a former Belgian police commissioner in Congo, who admitted to disinterring and cutting up Lumumba’s corpse before he dissolved it in acid. Soete later told Ludo de Witte, who wrote a book about Lumumba’s assassination, that he had taken the tooth “as a kind of trophy.”

Belgian authorities took possession of the tooth after Soete’s daughter showed it to journalists in 2016.

Whether the tooth is Lumumba’s hasn’t been verified by DNA analysis amid fears that DNA testing could destroy it. Speculation also persists as to whether the tooth comprises Lumumba’s only remains. De Witte said Soete boasted that “he took multiple teeth and part of a finger.” It isn’t known whether his claims are correct or where those remains are.

In 2020, a Belgian court cleared the way for the tooth to be returned to the family, shortly after Lumumba’s daughter, Juliana, wrote a letter to the king asking for the return of her father’s “relics,” calling him “a hero without a grave.” Juliana Lumumba didn’t respond to requests for comment.

Belgian officials have dubbed the tooth’s return “a new pivotal moment in the history of diplomatic relations between Belgium and the DRC, after the visit of King Philippe to the DRC in the second week of June,” De Croo said in a statement said last month. “The remains of Patrice Emery Lumumba refer to the common past between our two countries, including its difficult episodes.”

DRC officials haven’t replied to requests for comment about the tooth handover and its significance to the nation.