Nigeria’s Dependence on Central Bank Money Will be Hard to Cure

Nigeria’s Dependence on Central Bank Money Will be Hard to Cure

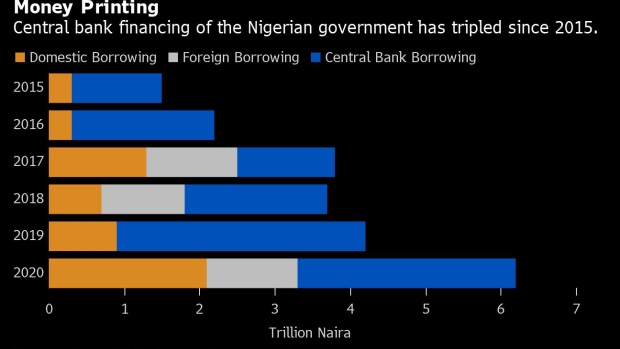

(Bloomberg) — The Nigerian government has become dependent on central-bank borrowing and will struggle to wean itself off the copious money printing that has raised concerns about the health of Africa’s largest economy.

After revenues collapsed during the oil shock of 2015, Africa’s largest crude producer turned to the central bank, borrowing about a third of its debt from the apex lender to cover a budget deficit that has tripled during the same time. Those loans, cheap and easily available, were not clearly reflected in the fiscal accounts and raised alarm bells at the International Monetary Fund and World Bank.

Unlike the vast amount of money released by monetary authorities in the U.S. and Europe, central-bank financing in Nigeria is driven by low revenues and used mostly to pay a swelling bureaucracy and a rising debt bill.

The IMF and the World Bank have said the practice undermines confidence and hampers investment. Uncontrolled money printing by central banks led to bouts of hyperinflation across Africa in the 1980s and 1990s.

Money printing in Nigeria has added to the excess liquidity pressuring the naira downward, forcing two devaluations, and pushing inflation to a three-year high in December.

Finance Minister Zainab Ahmed promised earlier this month to limit borrowing even as the country struggles with another fiscal crunch amid the coronavirus pandemic.

Central-bank financing dropped 12% from an all-time high of 3.3 trillion naira ($8.6 billion) in 2019, but still covered about half of the budget shortfall last year, according to government data and Lagos-based investment bank Chapel Hill Denham.

Unsustainable

“Without significant reforms to boost revenue, it’s going to be difficult to wean the federal government off central-bank financing,” said Opeyemi Ani, an analyst at Cordros Securities Ltd. “In the long run, it has consequences for macro-stability. It certainly isn’t sustainable.”

Ahmed and central bank Governor Godwin Emefiele last year vowed to eliminate central-bank lending by 2025 in a letter of intent to the IMF before the release of emergency financing.

Conflicting messages, however, have raised doubts about the government’s commitment to curb monetary financing.

Emefiele told reporters on Tuesday it would be irresponsible for the central bank not to finance the government when revenues plummet, and criticized Fitch Ratings for warning that more money printing could destabilize the economy.

“Emefiele’s rebuke of Fitch’s criticism shows that the CBN is in no rush to scale back central-bank financing of the deficit,” said Patrick Curran, an economist with Tellimer.

The first test for the government will be this year’s ambitious budget that bolsters spending by 26%.

Ahmed said the government will favor cheap local bonds, many offering real negative yields, over central bank borrowing and even international debt markets.

Fiscal Complacency

The government plans to convert the central-bank money to loans which would increase debt-service costs that already consume almost a third of actual revenues. Still, the rollback may help it in talks with the World Bank over the release of a long-delayed $1.5 billion loan.

The risk is that the overdrafts turn structural and remove incentives to bolster one of the world’s most inefficient tax collection systems, said Omotola Abimbola, a macro and fixed-income analyst at Chapel Hill Denham.

“The danger of central-bank financing is that fiscal complacency on revenue reforms continue to persist,” Abimbola said.