‘A question of dignity’: the pathologist identifying migrants drowned in the Med

‘A question of dignity’: the pathologist identifying migrants drowned in the Med

Dr Cristina Catteneo made it her mission to put a name to each man, woman and child found in the overcrowded hulls of sunken boats bound for Europe

At a glance, Dr Cristina Cattaneo assessed the lifeless body on the floor of an abandoned Sicilian hospital – a thin, young Eritrean refugee about 180cm tall. While most of the corpse was intact, his face and hands were skeletonised, probably the work of sea animals.

It was the morning of 3 July 2015, and this was the first body to be recovered by a navy robot after a shipwreck on 18 April that year, which left more than 1,000 people dead.

They came from Eritrea, Senegal, Mauritania, Nigeria, Ivory Coast, Sierra Leone, Mali, the Gambia and Somalia. They had been trying to reach Europefrom north Africa onboard a fishing boat with a capacity of about 30 passengers, which sank in the night after colliding with a Portuguese freighter that had approached to offer assistance. Only 28 people survived.

The vast majority of corpses were in the hull, wedged 400m deep on the sea floor. The boy’s cadaver was one of 13 the Italian authorities had found in the water and managed to recover using a mechanical claw. He was wearing a black jacket and sweatshirt, jeans and trainers. His remains were placed in a body bag and labelled with an identification number in white ink: PM3900013.

His identity is still unknown, like most of the hundreds of other victims. There is no official death toll but about half of the thousands of asylum seekers who have died while attempting to cross the Mediterranean lie in unmarked graves in Italy’s cemeteries.

Since 2013, Cattaneo, a professor of forensic pathology and head of Labanof (the laboratory of forensic anthropology and odontology) at the University of Milan, has been committed to putting a name to every man, woman and child who has drowned at sea. Her goal is ambitious, perhaps impossible, and has underscored the indifference of European countries towards migrants and how states discriminate against asylum seekers, even in death.

“Let’s imagine, just for a minute, that a plane full of Italians crashes off the coast of another continent,” says Cattaneo. “Let’s imagine that those corpses are recovered and buried without identification. We would never allow this. So why should we allow it if the ones who die are foreigners?”

Cattaneo believes that indifference towards identifying the bodies is a “cultural” question. “That most of the victims have dark skin and read the Qur’an is the likely reason why there is discrimination. In simple terms, we’re in two different contexts: one, our own, ‘rich’ European; and the other, ‘poor or foreign’.”

One of the first to raise the question of identification was Morris Tidball-Binz, who at the time was head of the forensics unit of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), and with whom Cattaneo had collaborated to identify lost and forgotten victims.

In February 2013, Tidball-Binz was visiting Milan. He phoned Cattaneo and, over lunch, confessed that the matter was consuming him.

“He told me that the ICRC had been receiving many phone calls from Syria and Eritrea from people who were expecting the arrival of brothers, children, girlfriends in Europe and who had never arrived,” said Cattaneo. “They were likely victims of shipwrecks and wanted to know how to find their bodies. He told me that the ICRC was conducting research in European countries to understand if there was a database for these people, and he asked me if there was a register in Italy. No, there was nothing. But the moment had come to create one.”

Early in 2014, the former government commissioner for the disappeared, Vittorio Piscitelli, signed a protocol with Labanof for the identification of refugees lost in the Mediterranean, and Italy became the first country in the world to do so.

“Those corpses were at the top of my mind,” says Piscitelli. “The cries for assistance from the families contacting us from across Europe and Africa for information on their relatives could not be ignored. When Dr Cattaneo showed me new technology that could be used for identification, I knew it was an opportunity that we couldn’t miss.”

The first step is the most difficult. On 3 October 2013, 368 people died off the island of Lampedusa. Hundreds of people were searching for their relatives. Cattaneo’s work would push her team at Labanof to the limit, as all of the difficulties in identification became apparent.

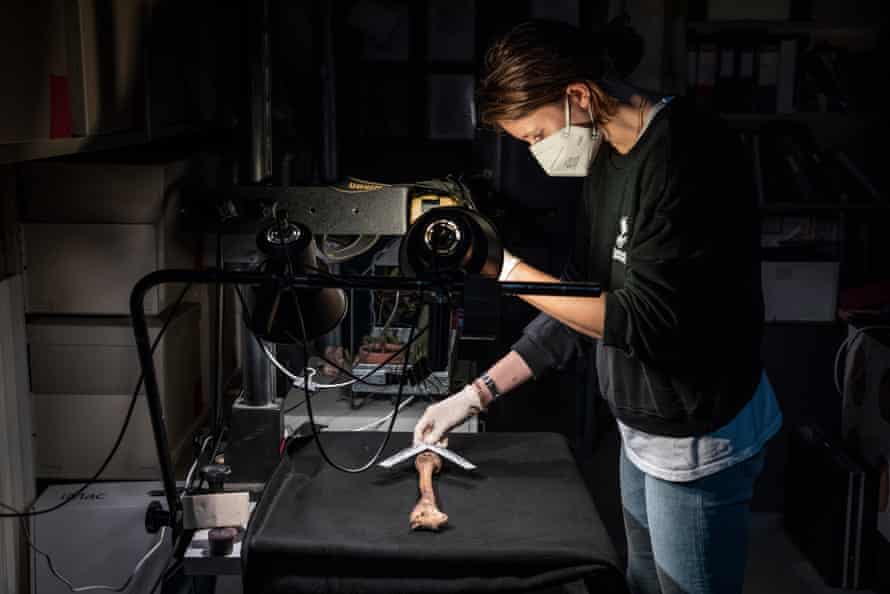

A postmortem is carried out to inspect the external tissues and internal organs, analyse bones and teeth, and collect DNA samples. Useful data, such as dental fillings, a tattoo, or disease are entered into a database.

The second step, called “antemortem”, is information from friends or family members. DNA from a close relative, an X-ray of a bone, or even a photograph is cross-checked with previous data.

“In theory, it’s very simple,” says Cattaneo. “Postmortem data plus antemortem data equals identification. But if one element is missing, it’s almost impossible to move forward. And for the migrants, we realised immediately that it is very difficult to find all of the right pieces.”

Precisely a year after the 3 October 2013 capsizing, in a first-floor office of the interior ministry in Rome, Cattaneo and her team met the first relatives of the refugees who perished near Lampedusa. In the following months, 80 families came forward and about 40 people were finally identified.

“It was a drop in the ocean,” says Cattaneo, a former PhD researcher at Sheffield University. “But it was important because we had given back the bodies of sons or brothers. We had given them peace. Identifying the corpses is not just a question of restoring dignity to the dead, it is also necessary for the health of the living.”

Family of the unidentified dead are often referred to as victims of “ambiguous loss”. Unresolved grief can generate psychological challenges such as depression or alcoholism.

Personal effects are recorded and then analysed. In a room in the forensic institute at the University of Milan, the Labanof team has dozens of shelves holding possessions found in the pockets of refugees who died at sea: necklaces, bracelets, photos, spare change, football team emblems, report cards. All catalogued.

“Migrants who have died at sea, often adolescents, have in their pockets the same objects that many of our teenagers have when we send them to school,” says Cattaneo. “The only difference is that they drowned while trying to reach our shores.”

In the abandoned hospital in Catania, while performing that first autopsy after the April 2015 shipwreck, Cattaneo noticed that the dead boy’s shirt had a pocket sewn up. It contained a small cellophane packet with a dark powder.

“It was sand,” says Cattaneo. “Sand from his village.”

A common practice among Eritreans is to take with them a physical reminder of their homeland before leaving, knowing they may never return.

The other bodies were recovered by Italian authorities in June 2016. The recovery itself became a public spectacle, as an entire section of the Italian navy was engaged in the operation and the work dragged on for months at a cost of €9.5m (£8.2m).

Inside the ship’s hull were more than 500 corpses, 30,000 mingled bones and hundreds of skulls.

“Imagine skulls and bones of hundreds of people closed in a metal box and being shaken for a year,” says Cattaneo. “That’s what we found, along with hundreds of decomposed bodies.”

Only six of these individuals have been identified so far. The search for relatives and friends has become increasingly complicated and funds are short.

“We’re working on it,” says Cattaneo. “But in order to complete our work, we need the support of other European governments.”

In April this year, the European parliament voted on a resolution for the protection of the right to asylum, which includes an amendment on the right of identification of people who die during the attempt to cross the Mediterranean and the necessity of a coordinated European approach.

At least four Italian universities, alongside the forensic service of law enforcement agencies under the coordination of Italy’s new commissioner for the disappeared, Silvana Riccio, continue the search to identify all of the victims of the April 2015 shipwreck, assisted by the ICRC and the Italian Red Cross. This disaster has become a symbol of sea tragedies, and the remains of the ship were displayed at the Venice Biennale.

Six years later, the body of the first migrant recovered from that shipwreck was buried in the cemetery in Catania. His tombstone bears the same number that was written in white on his body bag: PM3900013.

In the area near the Augusta wharf in Sicily, where, in 2016, firefighters set up tents to hold the corpses removed from the salvaged boat, there is now a meadow of pink wildflowers. Cattaneo’s diary, where the experiences of those first migrant autopsies are noted, contains a petal from the meadow.

“I collected it in Augusta, where I returned two years after the shipwreck,” Cattaneo says. “I always carry it with me, like that boy who took the earth from his village with him. That petal is my version of African sand. That petal is what nullifies the distance between me and him and that drives me, every day, to work in order to give that boy the name that has been stolen from him by Europe’s indifference.”