The Bamako Encounters 2022, Chapter 3 : African House of Photography

The Bamako Encounters 2022, Chapter 3 : African House of Photography

Rencontres de Bamako, chapter 3 – Dwelling made of grains of senevé

The Rencontres de Bamako – Africain biennal of Photography delivers a high-flying 2022 edition, focused on “multiplicity, difference, becoming and heritage”. Our correspondent Arthur Dayras reports on the third exhibition organized at the Maison africaine de la photographie, “Demeure faite de grains de senevé”.

The African House of Photography (MAP) was created in 2004 by the Malian state following the success of the first editions of the Bamako Festivals. Mali saw this as an opportunity to affirm the vitality of its photographic talent pool and the country’s primacy on the African continent in terms of photography. If one can say that Lagos dominates the cinematographic debates, that Dakar shines in contemporary art, Bamako is indeed the city of photography on the African continent.

Since its creation, this structure has developed activities such as printing and framing, digitization of collections, publishing of catalogs and artists’ books, photographic training and workshops with renowned artists. The African House of Photography does not seem to have any collections of its own, but remains an essential actor in the creation and exchange of photography in the country. The biennial regularly installs its exhibitions there, such as the current chapter three, “Demeure faite de grains de senevé”.

The hanging is meant to be collective, as in the exhibitions of the National Museum of Mali and the former railway station of Bamako. It is sometimes more difficult to grasp, the captions do not always immediately correspond to the series they illustrate, but we will forgive this facetiousness to visitors as the 2022 edition was complex to mount. The quality of the exhibition relegates this little inconvenience to the background.

The series “Sites of Africa” by the British artist Joy Gregory formulates a quest for memory on the places of British power, many of which harbor an unspeakable history, underlying, deeply rooted in a racist and colonial past. For example, the royal residence of Greenwich, which in 1596 was the scene of an edict by Queen Elizabeth banning the presence of “negroes”. It is an advertisement of 1769 of a certain John Bull selling a black child of eleven years, “with an excellent temperament and good dispositions” to the St. Clement Church. In an objective style, close to the Dusseldorf school, the artist takes on these places of power and delivers through her message all the ambiguity of this silenced past .

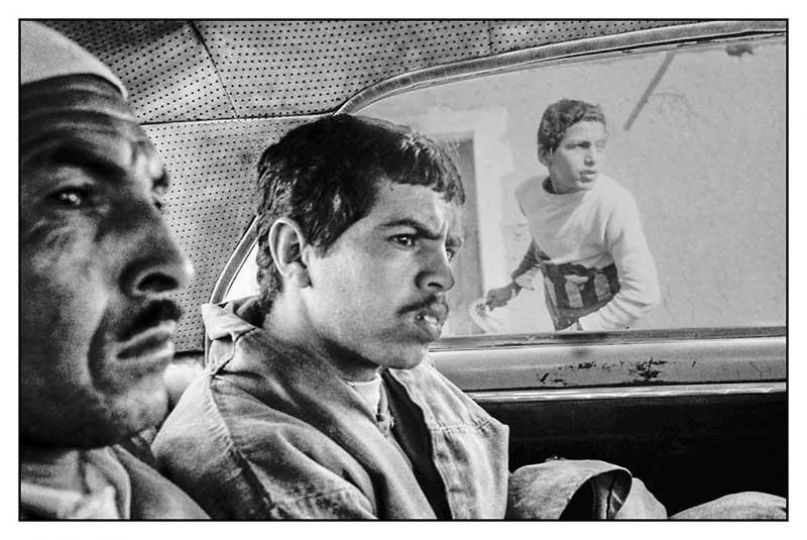

The large place given to Joy Gregory in the exhibition is entirely justified, as is the place given to Daoud Aoulad Syad. In 1990, the Moroccan photographer and filmmaker was acclaimed by Henri Cartier-Bresson, who encouraged him to pursue his work. The Western public knows him in particular for his 1989 edition by Contrejour, Marocains, and for his exhibition at the Maison Européenne de la Photographie in 2015. His African colleague has dedicated three beautiful walls to him, where the power of street photography with humanistic accents is revealed.

Daoud Aoulad Syad makes each image a decentered narrative, anchored in a poetics of the moment, of immediacy. The catalog summarizes it in a beautiful expression, “a multitude of snapshots”. To put it simply, there is in his work all the flavor of street photography: faces, expressions, games and tensions, life in short surveyed in a restricted territory, explored in its smallest corners. We believe in it, we smile about it. The photographer also excels in the art of portraiture, with a touch of humor in his staging and compositions.

Another Moroccan artist, Imane Djamil gives to see the coastline Tarfaya and resonates with the mythology of Atlantis. The city and its heritage are falling into ruin, neglected by the public authorities, accentuated by the growing desertification of the Sahara as well as by the exodus. The artist underlines by his stagings the failure of the State to seize a heritage inherited from the colonial time, just like the impossible life of the populations abandoned in this part of Morocco. The quality of the series is due in large part to the soft, pastel tones of the prints, many of which seem unreal, even when they are inhabited by tiny scenes.

Lucia Nhamo’s filmed performance on the rocks of the Chiremba Rocks National Heritage Site in Zimbabwe is worth seeing. There she tries as best she can, clad in a loose, heavy and deliberately constrained garment, to roll along the curve of the rock. Her attempt symbolizes the powerlessness of her body crushed by the weight of power, itself evoked by the honor guard in the background at the end of the video. A video that echoes the concerns and gestures of an equally powerful work by the Brazilian Anna Maria Maiolino, Um Dia (1976)* in its silent protest, embodied by the body, of military oppression.

The highlight of the exhibition is the video Mourn by Ixmucané Aguilar. With a single fixed shot, the artist films the obstinate march of a group of Herero women in the desert. They advance in the silence of the wind to celebrate their ancestors in the dunes of Swakopmund (Namibia), where there is an open memorial for the victims of concentration camps under the German colonial regime. The simplest way is still to do without words.